Diagnosing Dyslexia

When approaching final diagnoses, there are typically multiple errors in discovering dyslexia as the underlying illness. They are either misdiagnosed or the diagnosis is missed entirely. For one, the indicator during testing is simply not enough. The mere use of the IQ-achievement discrepancy model to determine if an individual is dyslexic is far too narrow of an approach.

In fact, having dyslexia is completely irrelevant to one’s overall intelligence. To prevent such a setback, psychologists and neurologists should include multiple indicators or models to improve the reliability of the diagnosis. For example, testing both behavioral and biological factors in combination with the RTI model. Biological testing is critical to predicting whether a child has dyslexia as 80% of dyslexia is genetically inherited (Dyslexia Advocacy Action Group). Additionally, it is important that if the early signs of dyslexia are exhibited in a child (reference FAQ section), then it is the responsibility of the guardian(s) to have them screened.

Late detection of dyslexia can not only inhibit the child in school but socially and emotionally. "Research conducted by Dr. Kenneth Kavale of the University of Iowa and Dr. Steven R. Forness of the University of California at Los Angeles indicates that as many as 70% of children with learning difficulties suffer from poor self-esteem" (March 18, 2016 Print Article. "Learning Disabilities and Psychological Problems: An Overview." Parenting. Web. 31 Mar. 2017.). Many dyslexic students will suffer from anxiety and depression because of their difficulties inside and outside of the classroom. According to the Research Excellence and Advancements for Dyslexia Act (READ Act): Students with learning disabilities including dyslexia have a three times higher risk of attempting suicide. Dyslexia should be identified early, as a plan for intervention can be made.

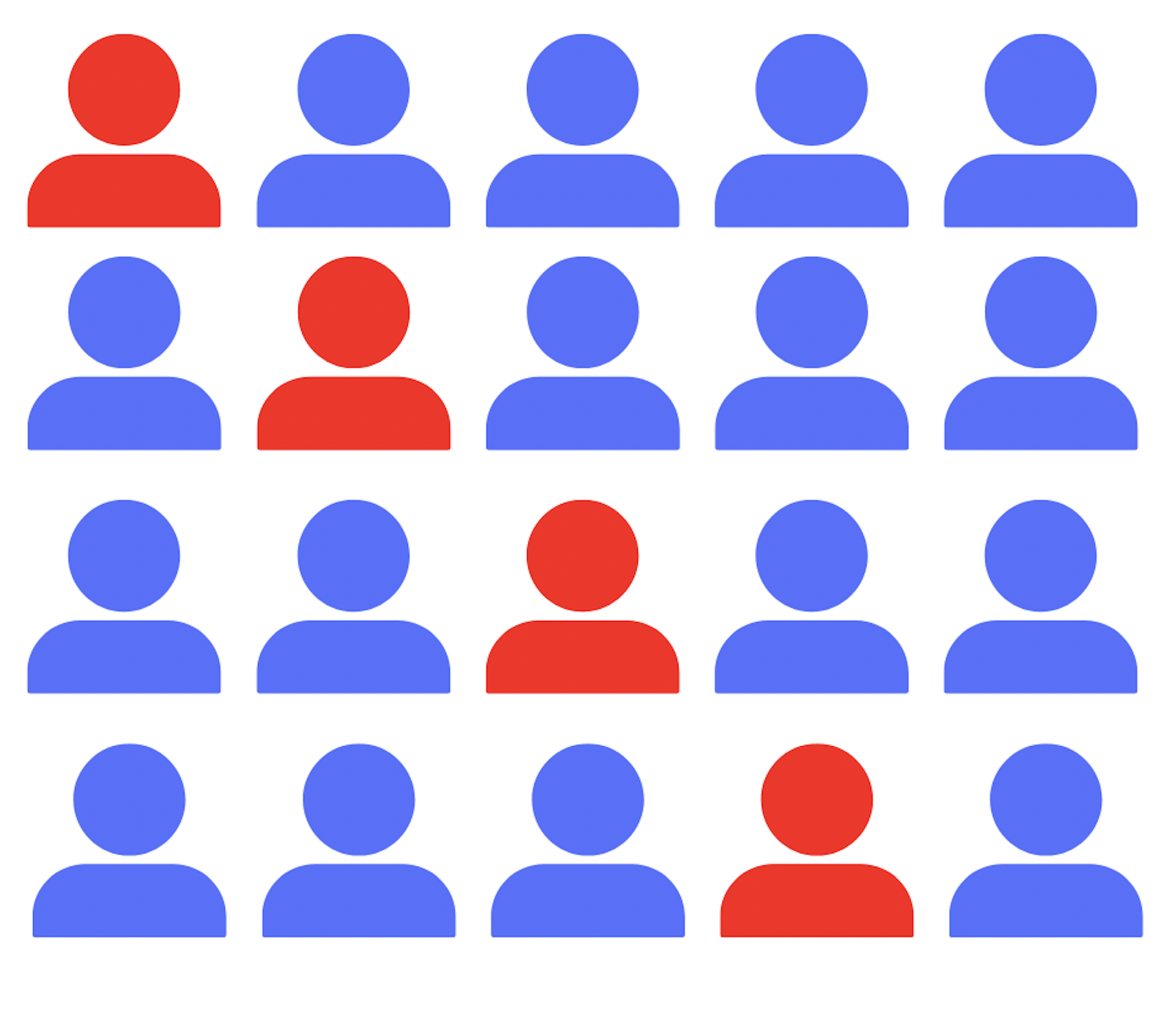

1 in 5 people have dyslexia but only 1 in 20 are properly diagnosed.

Mental Health & Comorbidity

Although it is possible that one may exhibit both, dyslexia is often mistaken for alternative mental illnesses. Dyslexia can cause a child to feel anxious, depressed, or have low self-esteem. These emotional issues stem from dyslexia, however, it is often mistaken for the other way around. Psychologists during screening may mistake symptoms of mental illness for solely the emotional disorder, without recognizing the underlying issue: Dyslexia.

In the case of comorbidity, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) can correlate with dyslexia in the way that both can be present. The reason these two are commonly mixed is the lack of attention which can lead to academic “underachievement”. “Approximately 20–40% of children with the inattentive subtype of ADHD have [Reading Disorder]” (Frontiers in Psychiatry). The reason for the comorbidity of ADHD and dyslexia is the shared genetic risk factors. To treat comorbid conditions, both conditions must be targeted. Commonly, psychiatrists will treat one symptom, but leave the other unattended. During the intervention, it is important to detect and focus on dyslexia because, oftentimes, it is the cause of the alternative problem.